Teach Me How to Say Goodbye

When I first started voting, weeks after I turned 18, I didn’t get a sticker. My polling place, walking distance from my childhood home, didn’t give out stickers. It was 2014, and it was the old normal. My Facebook feed wasn’t overwhelmed with voting sticker selfies the same way it’s been in recent years. The words “President Trump” had not been said, and if they were, it was probably because of someone’s fever dream. I hadn’t gotten into college yet, I hadn’t left my gap year early, I hadn’t moved to Washington Heights.

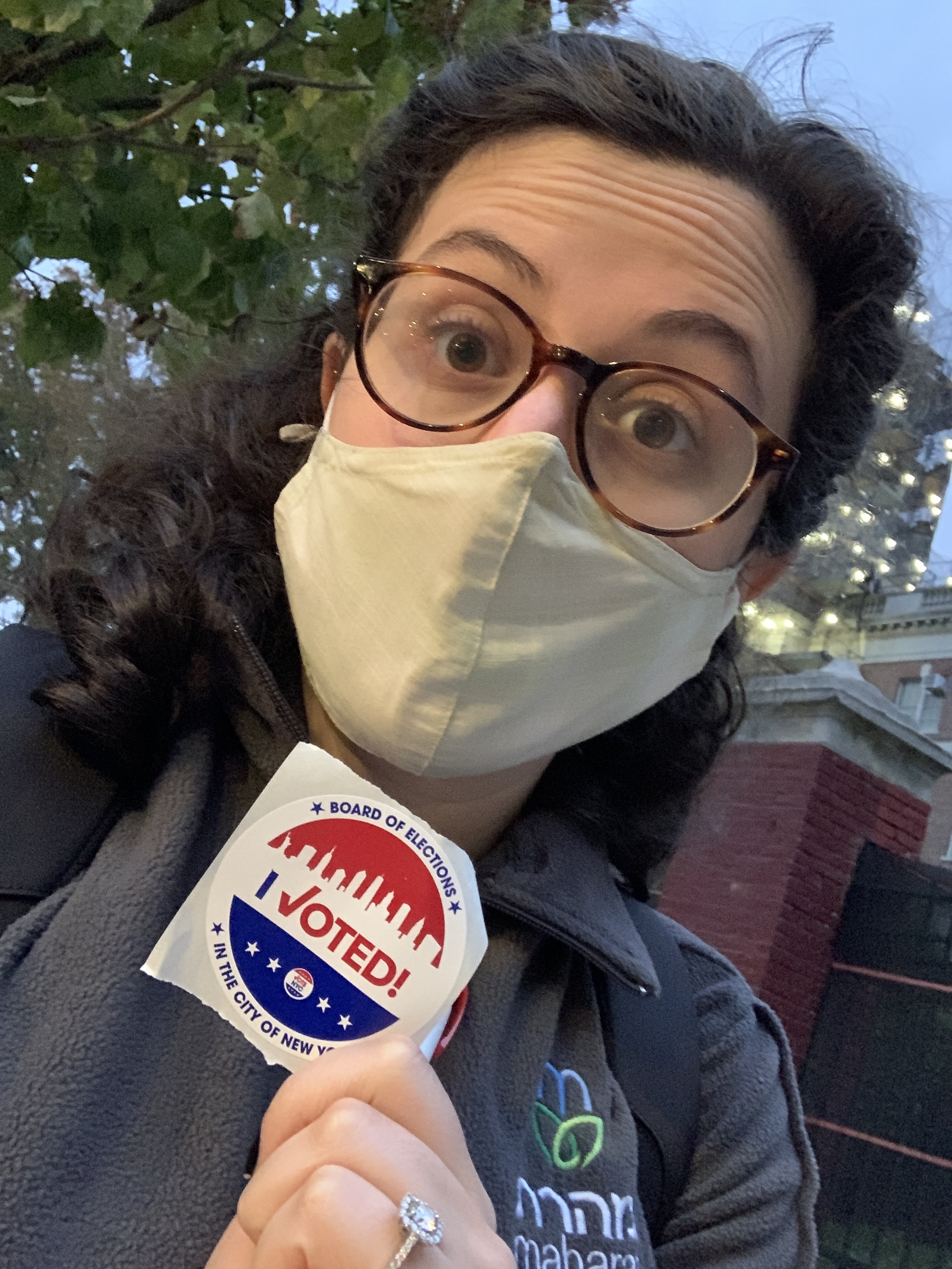

Now I have three “I Voted” stickers on the bulletin board in my third Washington Heights apartment. These stickers are only from elections that took place within the last year. I voted in the primaries this summer, as well as in the presidential election in 2020 and the regular general election yesterday. I’ve now voted and gotten stickers more times than I’ve voted and not gotten one. I had been a wannabe New Yorker most of my life; voting in New York allowed me to try on that identity for real, to actively participate in New York political discourse, to make the Heights my home.

And now I’m standing on the ledge, waiting for my new nascent identities to take shape and make themselves known. I’m preparing to detach from and let go of “the city” and my uncoupled self. I’m still not sure what name will appear on the driver’s license I finally plan on earning this year – and that is a wild, bonkers, absolutely bizarre sentence for me to write.

Because I fell in love in New York, I am now preparing to leave it. There is so much I don’t know about this impending move: there’s a staggering number of metaphorical balls in the air that the 20-year-old who first put down roots on Wadsworth Avenue would’ve been overwhelmed. I’m still overwhelmed, don’t get me wrong, but I’ve gotten exponentially better at juggling, because that’s what the past few years have been: a crash course in balancing varied priorities while also growing up.

The girl who moved into a fifth-floor walkup had no way of knowing how the choices she was making – and continued to make – would have a profound impact on the path she had decided she was on. Within a year, she’d decide she didn’t want to teach high school English, she wanted to teach Torah, and she’d go on to drop her Education major a year after that. The rabbinate was not on her radar, and when it was occasionally brought up, she denied it. She’d already fallen in love when she moved, in fact, her boyfriend helped her unpack. Her best friend came and visited her a few days later, and they fell asleep back-to-back on a twin mattress, both thrilled by the glittering grown-up world just waiting to be explored.

And now here I am. Those two most important relationships I had four years ago are no longer. I’ve fallen out of love and mourned what was. I’ve actualized the dreams I first felt as nagging doubts in my gut, because I allowed myself to tune into my deeper self. I’m in my second year of rabbinical school and already starting to dream about what I will do with my semicha. I’ve watched and participated in numerous transitions in the community that brought me to the Heights.

And then there are the smaller things: I’ve gotten stuck on so many subways, and I’ve been asked for directions by tourists. I’ve cheered until I got hoarse as I marched down Ft. Washington Avenue after Biden won the election. I’ve complained about events in Brooklyn and been on awkward first dates in midtown and the Upper West Side. The music behind my building has kept sleep from me, and I’ve learned how to blame DeBlasio for inconveniences.

I’ve walked down an eerily empty avenue to get to the bank, feeling like a character in a dystopian movie because of the ubiquitous masks and feet-shaped indicators on the sidewalks. I’ve opened my window and banged a frying pan with a metal spatula, because in the beginning of this pandemic, we were able to be both scared and thankful together. I’ve stayed when it felt like everybody else was leaving, fleeing to the suburbs and their parents’ embrace.

And as the world started to open back up, I did too. I redownloaded dating apps and let myself realize that I was ready to grow up and grow into a relationship. I met a guy and told him I loved him the same day we met each other’s’ parents. “It’s not not serious,” I said to my rabbi.

“So it’s serious,” he responded, and I laughed. Because of course it was, even though I couldn’t articulate that then. Only something serious and real could be the force that enabled me to step back from running a shul, to consider leaving a city where my heart still beats in tandem with the traffic lights and click-clack of subways arriving. Only something serious could allow me to graduate from living with roommates, to write this blog post, to – come July – let go of New York.